|

The Federal City in its Early DaysPart I - Construction & Combustionby Erik James OlsrudThe following is a chronology of Washington DC's early development and a description of what a visitor or resident would have seen from 1790-1830. This data may be of use to interpreters portraying a character from the vacinity of Washington or an officer who had visited the city, or for teaching the public about exactly what it was that the British had burned down in August of 1814. The English translation of the Algonquin word Potomac is "meeting place." A better name could not be found for the river which flows along the heart of a democracy's capital, astride the boundary of the Northern and Southern states. The settlements of Georgetown and Alexandria predate Washington, so there was already a small Euro-American population in the area. Georgetown was a thriving tobacco port founded in 1751 George Washington proposed this swampy, wooded area as the national capital city in 1790. In that year he met with local landowners at the Elusive Tavern to convince them to sell the land that would become the Federal Territory. Maryland and Virginia were eager to benefit from the growth, business, and influence that an adjacent capital city would offer. Both states ceded, free of charge, land sufficient to form a 10-mile square territory. Maryland contributed $72,000 and Virginia $120,000 for initial development. Virginia's section was retroceded back in 1848, which is why the city is not square anymore. All of the public buildings are on the Maryland side. Pierre Charles L'Enfant, a Frenchman, was contracted to plan the new city. He set it out on four quadrants with major avenues leading into the center of the city. The street arrangement proved confusing and unpopular. The term "avenue" was an old European term for the shaded approach to a countryside estate; L'Enfant's plan was the first use of the term for urban addresses in this country. The major avenues were named for states. The primary thoroughfare of the public section was named Pennsylvania Avenue as compensation for Philadelphia, which had lost its bid to be the nation's permanent capital. Pennsylvania Avenue ran through Tiber Creek, which was described as a deep morass covered with elder bushes. Crossing the avenues were streets named with letters. There is no J Street, for the same reason there is no company J in army regiments; 'J' looked too much like an 'I' when handwritten. I Street was often written Eye Street to avoid confusion with 1st Street. L'Enfant reported to Washington on June 28, 1791, "After much menutial search for an eligible situation, prompted, I may say, from a fear of being prejudiced in favor of a first opinion, I could discover no one so advantageous to greet the congressional building as that on the west end of Jenkin Heights, which stands as a pedestal waiting for a monument." Commissioners Thomas Johnson, Daniel Carroll, and David Stout proposed the name of the city to L'Enfant: "We have agreed that the federal district shall be called 'The Territory of Columbia', and the Federal City 'The City of Washington'." George Washington supposedly, and modestly, continued to refer to it as the Federal City. Thomas Jefferson bluntly called the proposed site for the city "that Indian swamp." William Thorton won the architectural competition to design the public buildings. In 1803 Thomas Jefferson appointed Benjamin Latrobe Surveyor of Public Buildings, and Latrobe clashed with Thorton for fourteen years over the development of the city.

The Congressional Building, 1818 George Washington laid the cornerstone for the capitol on September 18, 1793. However, no one now has any idea where that cornerstone is located. The original capital, called "The Congressional Building", was about one-third the size of the current structure. The Senate and House chambers were finished by 1812. The first dome, a dark wooden structure, was built by Charles Bulfinch and was finished in 1829. It must have taken a long time to build because it is visible in this 1818 drawing. The current large iron dome was under construction during the Civil War. The capitol was cramped; both houses met upstairs, and the Supreme Court presided in the basement. The lack of light and ventilation in the lower floors was blamed for the premature deaths of many lawyers and jurists. The Library of Congress and the Supreme Court library were also contained within the structure.

The President's House, 1818 "The White House" was a term applied to the President's residence by Theodore Roosevelt. In the early nineteenth century, it was called simply, "The President's House." The cornerstone of the President's House was laid in 1792. John Adams first occupied the house in 1800, and it was finished in 1802. Severely burned by the British in 1814, the interior was rebuilt from 1815-1817. The South Portico was added in 1824, and the North Portico followed in 1829. L'Enfant planned a 400' by one-mile mall encompassing paths and monuments, but it was not landscaped until the 1850's. A canal, and later railroad tracks, crossed the National Mall until it was landscaped into a park. Latrobe's 1815 map of the mall bears no resemblance to the 2002 appearance; the entire West end of the modern mall, including the current site of the Lincoln Memorial, was part of the Potomac River in 1815. L'Enfant imagined a giant equestrian statue of George Washington on the mall. After Washington's death, a favored proposal was a 100' square pyramid mausoleum, but Mount Vernon would not surrender his casket for such a project. The current obelisk monument was begun in 1848, left unfinished from 1854-1876, and at its completion was the tallest man-made structure until eclipsed by the Eiffel Tower. The monument was begun near the bank of the Potomac, but by the 20th Century the riverbank had been moved hundreds of yards West, doubling the length of the Mall.

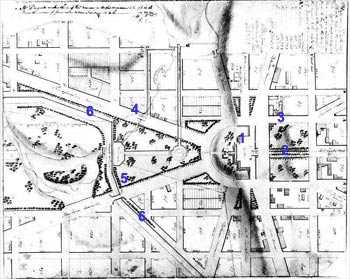

Latrobe's Plan of the Mall and Capitol Grounds, 1815

1 The Congressional Building (The Capitol) The government set up shop in its new home in 1800. Secretary of the Treasury Albert Gallatin wrote of the city in January 1801, "Our local situation is far from being pleasant or even convenient. Around the capitol are seven or eight boarding houses, one tailor, one shoemaker, one printer, a washing woman, a grocery store, a pamphlet and stationery shop and an oyster house. This makes the whole of the Federal City as connected to the capitol." Benjamin Latrobe described the city in 1806, "In cases of extreme poverty and distress, workmen are found in extreme indigence, scattered in wretched huts over the waste that the law calls the American Metropolis." In February 1801 the Federal Territory was designated the District of Columbia. The district grew steadily, as follows:

What Goes up Must Burn Down On 24 August 1814, British troops entered the city. As British General Robert Ross passed Robert Sewall's house, near the present site of the Supreme Court building, a shot rang out and killed the General's horse. Angered, Ross ordered the house burned. The Navy Yard on the Anacostia River had already been set afire by the Americans to prevent its capture, and the Brits finished what was started, by burning the rest of it. Events got a little out of hand, and most of the public buildings went up in smoke. Elias Boudinot Caldwell, Clerk of the Supreme Court, saved the Supreme Court's library by moving the books into his house before the Congressional Building burned. Likewise, as everyone knows, Dolley Madison saved a portrait of George Washington by carrying it outside before the burning of the President's House. The Library of Congress lost its books in the blaze, which were later replaced with the purchase of Thomas Jefferson's personal library. British officers dined at the Rhodes Tavern on the evening of the 24th without candles, eating their meal by the light of the conflagration arising from the nearby President's House. William Thorton, designer of the Capitol and the Superintendent of Patents in 1814, claimed to have saved Blodget's Hotel, site of the Patent Office and the city's first theatre. According to himself, he declared, "Are you Englishmen or Goths and Vandals? This is the Patent Office, the depository of the ingenuity of the American nation, in which the whole civilized world is interested. Would you destroy it?" The British did not torch the hotel, but it did burn down accidentally in 1836. The mammoth FBI building now looms over the site. The National Intelligencer, a daily newspaper published by Joseph Gales Jr., met a different fate. British Admiral Sir George Cockburn ordered the building demolished because Gales had printed unkind editorials about him. To spare adjacent houses, the office was pulled down instead of being burnt. All of the papers therein were carried outside and put to the torch. After the burning of the public buildings, Congress met in a hastily built brick building from 1815 to 1819 as the smoldering Congressional Building was repaired. This "Old Brick Capitol" was the site of Monroe's inauguration in 1817. John C. Calhoun died in the building, then a boarding house, in 1850, and it was a prison during the Civil War. "The Star Spangled Banner." written by Francis Scott Key at the battle of Baltimore Harbor, was first sung in Washington at a retirement party for Secretary of the Navy William Jones on December 14, 1814, at the McKeown Hotel. According to the Intelligencer, "Key's very beautiful and touching lines were sung with great effect by several of the guests". This was after twenty-one toasts had been quaffed to honor Jones. The McKeown Hotel stood on Pennsylvania Avenue near the current site of the National Archives and the Canadian Embassy.

Part II - Places to Go, Things to See

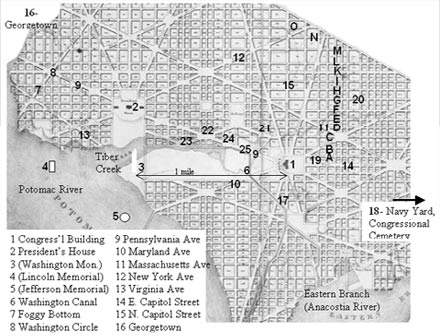

Part I of this series examined the design and construction of our nation's new capital from 1790-1814. Part II lists sites that a visitor to Washington may have seen between 1790 and 1830. This data may be of use for anyone interpreting an Easterner or military officer. Sites are numbered and labeled on a cropped copy of Robert King's map of Washington, 1818. Most locations are approximate. Modern monuments are added as points of reference- note that the Western half of our modern National Mall was in the river in 1818.

Chain Bridge. Just west of the city a series of eight bridges crossed the Potomac at the same spot. The third bridge was suspended on two thick iron chains from stone towers. It flooded out in 1812, but the following five bridges were always called "The Chain Bridge". 16- Columbian Foundry, 1800. Located in Georgetown. Built by Henry Foxall, a Methodist minister and Mayor of Georgetown. The foundry produced up to 300 cannons and 30,000 cannonballs annually. The Ten Commandments were carved into slabs of stone in the building's foundations. 18- Congressional Cemetery, 1807, was called "America's Westminster Abbey". Each Congressman was to be assigned a plot, which became a morbid joke among members. J. Edgar Hoover and John Phillips Sousa are buried there. Located near RFK stadium. 1- Daniel Rapine Bookshop, 1801, a bookstore near the capitol. The site was later engulged in an expansion of the capitol building. 7- Foggy Bottom A swampy riverfront area inhabited by Blacks, and Irish and German immigrants. Site of docks, breweries, and manufacturies. The 'water gate', a gate to the Potomac, regulated water levels in the city canals. Currently the site of the Watergate office building and the JFK Center for the Performing Arts. 7- Georgetown University, 1789. The nation's oldest Catholic and Jesuit University. Located on 38th Street and O Street on the Potomac River. 7- George Washington University, founded in 1822, moved to Foggy Bottom in 1912. Now located south of Washington Circle. Holmstead Racetrack, 1802. Designed by William Thorton, designer of the Capitol building. Up to 10,000 spectators watched National Jockey Club races in the 1820's and 1830's. Located west of the city. 18- Navy Yard, 1799. Located in the Anacostia River (then called the Eastern Branch). The Americans set the yard alight as the British approached in 1814, to keep it out of enemy hands. Pierce Mill, 1820-1897. The mill ground 70 bushels of grain daily. It was abandoned when the Potomac shifted course and the mill run dried up. Located west of the city. 19- Post Office Lund Washington Jr., son of a cousin of George Washington, served as city postmaster in 1796. He operated the post office in his house, near the current Supreme Court building. 6- Washington Canal, 1815. Running along the north side of the mall, its main use was as an open sewer. It never carried as much commerce as was initially planned. This was also the location of "Hooker's Division" during the Civil War, when General Hooker relocated the city's prostitutes here. Made obsolete by the railroads, the canal was filled in 1870. 8- Washington Circle. Confluence of 23rd Street, Pennsylvania Ave, and New Hampshire Ave. 21- First Presbyterian Church, 1827. Presidents Jackson, Polk, Pierce, and Cleveland worshiped at this church. Between C and D Streets. 21- First Unitarian Church, 1822. Boasted the first churchbell in Washington, cast in Paul Revere's foundry. John Quincy Adams attended. Located on D Street. 16- Mt. Zion United Methodist Church, 1816. This Black Georgetown congregation was a destination of freedom for escaped slaves on the underground railroad. 16- St. John's Church, 1796. Located in Georgetown. Francis Scott Key was a church vestryman. 23- Carusi's, c. 1820. Presidents held their inaugural balls at Carusi's from J. Q. Adams through Buchannan. Harrison caught his death of cold at his inauguration here, and after 1841 the hotel was known as "Harrison's last dance". Boston Mayor Josiah Quincy noted that he saw a waltz for the first time at Carusi's in 1826. 18- Elizabeth Leslie's Tavern, c. 1800. Located near the Navy Yard's thirsty laborers. 24- Indian Queen, 1820, was a most splendid hotel, and the first in the city with a bridal suite. A contemporary review said, "Remained for many years Washington's leading hotel, kept by Jesse Brown, the Prince of Landlords, personally presiding at table, at which decanters of brandy and whiskey were served without extra charge." 18- Joseph Wheat's Tavern, c. 1800. Located near the Navy Yard's thirsty laborers. 24- McKeown Hotel, Hosted the first singing of the 'Star Spangled Banner' in December, 1814. Located on Pennsylvania Avenue. 24- National Hotel, 1826. An enormous 200-room hotel made by combining six adjacent row houses. Henry Clay died in this hotel in 1852. Rhode's Tavern. British officers dined here on August 24, 1814 after setting alight the nearby President's house. 25- St. Charles Hotel, 1820. Visiting Indian delegations from the West lodged here on occasion. Members of Congress lodged here. Located on the canal at Pennsylvania Avenue. French geographer and surveyor David Baillie Warden wrote of Washingtonians in 1816, "At dinner and at tea parties, the ladies sit together, and seldom mix with the gentlemen, whose conversation naturally turns upon political subjects". Also, "Both sexes, whether on horseback or on foot, wear an umbrella in all seasons." A topic of considerable debate was the healthiness of the city. It was much healthier than New York and Philadelphia, which were furiously scourged by Yellow Fever in the summers of the 1790's. But, Washington was less healthy than most small northern towns. Those who wanted the capital to move to Washington emphasized its healthiness. Even though Washington is hot in the summer, it was a getaway destination for people fleeing the fever in Philadelphia. Thus this strange quote from a newspaper in July, 1800: "The intense heats of the season, actually remind us of the immense superiority which the City of Washington will enjoy, even when it shall become populous, over every other city, perhaps, which ever existed, in its numerous open grounds and the noble spaciousness of its streets and avenues. These are advantages in point of health and pleasantness which come home to the feelings and for the want of which wealth and grandeur cannot compete." Massachusetts Congressman Theodore Sedgewick wrote of the Washington site in 1789, as an argument for keeping the capital in Philadelphia: "The climate of the Patowmack is not only unhealthy, but destructive to northern constitutions. Vast numbers of northeastern adventurers have gone to the Southern states, and all have found their graves there. They have met destruction as soon as they arrived." Land developer William Cranch wrote to his mother in 1794: "You have been misinformed with regard to the fever raging in this city. There is no prevailing disorder here at present. The number of deaths has been remarkably small considering the number of workmen here and considering their mode of life, their imprudences, and their bad provisions." General James Wilkinson wrote in Washington in 1800, "The heat here for a few days past has exceeded my experience, and unhinged all my faculties rational and sensual." Washington was a beautiful city in its early days, but the most common complaint was a lack of housing, which forced even congressmen to share rooms in boarding houses. Jacob Wagner, chief clerk of the State Department, wrote in 1800, "The comforts of this place daily diminish, and the fall is very sickly. Beside the high price and scarcity of manufactured and foreign articles, the produce of the country is not to be had in plenty." Margaret Bayard, newly arrived to the city and wife of newspaper editor Samuel Smith, was forced to live in a hotel due to lack of housing. She wrote in 1800, "No one who removed to Washington, will be exempt from the same difficulties; people of fortune and fashion, it there are no houses, must go to lodgings, and must live in unfinished buildings. This will not be the result of poverty, but of local circumstances, which must affect the rich and the poor." Abigail Adams was at first hesitant of moving to the President's House, thinking it too large to be adequately heated and thereby naturally unhealthy. However, when she arrived, she wrote, "The President's House is in a beautiful situation in front of which is the Potomac with a view of Alexandria. The country around is romantic but wild, a wilderness at present." How the city has changed!  "On the Spot: Pinpointing the Past in Washington, DC", Douglass Evelyn and Paul Dickson; National Geographic Society, Washington, DC; 1999. "Washington DC Past and Present", Peter R. Penczer; Oneonta Press, Arlington, VA, 1998. "Map of the City of Washington in the District of Columbia", Robert King, 1818. "Plan of the Mall and Capitol Grounds", Benjamin Latrobe, 1815. DC Heritage Tourism Coalition, www.dcheritage.org Georgetown University web site, www.georgetown.edu George Washington University web site, www.gwu.edu "When Washington was the place to be in the summer", article by Bob Arnebeck, members.aol.com/swamp1800, an excerpt from the book "Through a Fiery Trial: Building Washington" by Bob Arnebeck, Madison Books, 1991 |